Italo Calvino the Art of Fiction No 130 Pdf

By Rosa Nussbaum

My desk is a chip like an isle: it could just besides be in some other country every bit hither.

—Italo Calvino

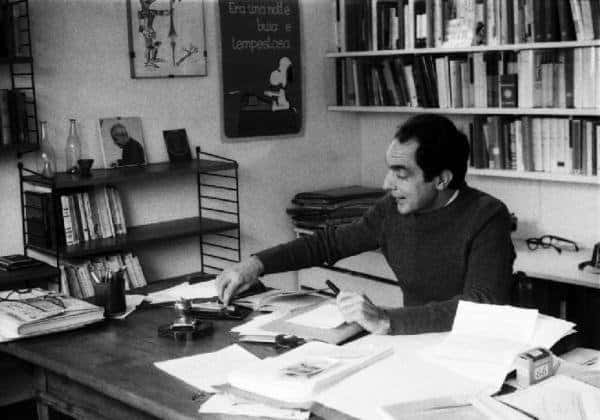

Thehere in question is a narrow room occupying the meridian flooring of a three-storey house on the southern fringe of Montparnasse. Heavily laden bookshelves and strategically placedobjets extend forth the length of 1 wall, framing the doorway. Where the shelves reach the ceiling a pitched roof slopes down to meet a line of s-facing windows and a door leading to a small-scale roof terrace. The desk-bound itself is a sturdy wooden matter positioned towards one end of the room. It tin can exist approached from all sides, giving it the air of a dependable kitchen tabular array that has been granted a second lease of life. A chair to 1 side orients the sitter towards the window with their back to the door. At the other end of the room is an informal seating expanse where a mean solar day bed and several armchairs are grouped around a low java table.

Despite its urban setting Calvino liked to refer to this residence as his 'country home', a place of confinement where he could conduct his piece of work in isolation. This feeling arose from a sense that the cultural and literary image of Paris was and so dense that information technology effectively ceased to be as a potential bailiwick in the imagination of the author. It became 'a city without a name', at least in relation to his working life, which remained 'entirely in Italy'. Tied up in this perception is the firm atop which Île d'Italo was perched. When Calvino arrived in 1967 it was in the company of his wife Esther and their girl Giovanna, then two years old. Paris was the backdrop against which 'small applied bug of family life' unfolded – perchance a somewhat euphemistic way of describing the experience of sharing one'southward home with a toddler. Esther worked as a translator for UNESCO and the young family employed a maid to go along the firm ticking over. When they eventually returned to Italia in 1980 it was due in no small part to the loss of this employee, after which according to Esther 'life became a catastrophe'.

If Paris was defined for Calvino during this period generally by the fact of its not existence Italia, so the atmospheric condition which allowed it to remain so in his listen were inextricably linked to the smooth direction of his domestic affairs. 'When I am in Paris you could say I never exit this written report,' he noted in 1974, suggesting a focus which radiated out from the desk to take in the residual of the room only not the rest of the business firm. Sara Ahmed has written that we orient ourselves 'towards certain objects, those that aid us find our manner'. Using the example of Edmund Husserl's description of his ain desk, Ahmed notes how 'the family habitation provides…the background confronting which an object (the writing table) appears in the nowadays, in forepart of him'. Such an orientation is only made possible by 'the work washed to keep his desk clear, that is, the domestic work that might be necessary for Husserl to turn the table into a philosophical object'.

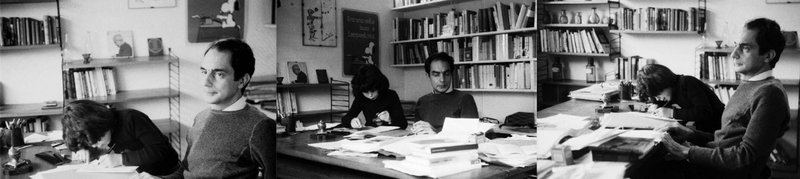

Equally anyone who works from home is well aware, balancing professional person and domestic spheres can be a challenge. In a serial of photos taken by Carla Cerati from the same year, we see a relaxed Calvino together with his family unit in the study – Giovanna hunched over the desk next to her father, or else squirming around on his knee as Esther looks on. Some other image from this fix shows Calvino seated alone backside the desk-bound, a blank piece of paper laid out in front of him and his pen poised tantalisingly over an ink well, as if Cerati had tried to crystallise the precise moment that precedes an human action of literary invention. But closer examination of the contact sheet shows Calvino interacting with someone outside the frame whilst Cerati works on the composition: perhaps Esther offering some management on the staging or Giovanna chiming in with a question. Whether nosotros can sustain an orientation towards the writing table, Ahmed concludes, is dependent on those forces which conspire to pull our attention abroad from it. All this is to say that the places where we choose to work, and by extension the surfaces nosotros piece of work on, are crucial insofar every bit they can help us discover our manner, whether by virtue of their orientation towards or away from the other spaces nosotros inhabit.

But what if they aren't up to the job? We do not know much about the provenance of this cartoon, except that for a fourth dimension it was attributed to Thomas Chippendale. Seemingly the author was so dissatisfied with their existing piece of work surface that they decided to devote considerable energy towards reimagining it. A pair of swan-neck handles on the front panel would seem to situate the piece in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, and one of the annotations informs us that the desk was intended to be used for writing. A hinged top covered with green textile conceals a hollow interior, attainable past sliding the front department of the desk-bound forward. The writer permits usa to peer inside past choosing to represent the desk from in a higher place, its hinged lid neither fully open up or airtight. In this intermediate position the panels are reminiscent of a pitched roof; a change in scale which renders the diverse compartments within into a serial of rooms that offer increasing privacy as they recede further into shadows below the eaves.

If you subscribe to the one-time adage that a tidy desk signals a tidy mind, so the author of this drawing must take harboured dreams of a spotless interior landscape. The internal compartment is annotated in a somewhat obstinate tone with diligently assigned labels for each of the 4 identical drawers. Further 'divisions for papers' bring much needed order to the veritable no human's country of 'open space for longer papers', indicated towards the front. We are given no clues about the room where the desk is situated, nor can we tell if its internal compartments were ever put to use as intended, only that their number and arrangement points to a high regard for both prolificacy and lodge.

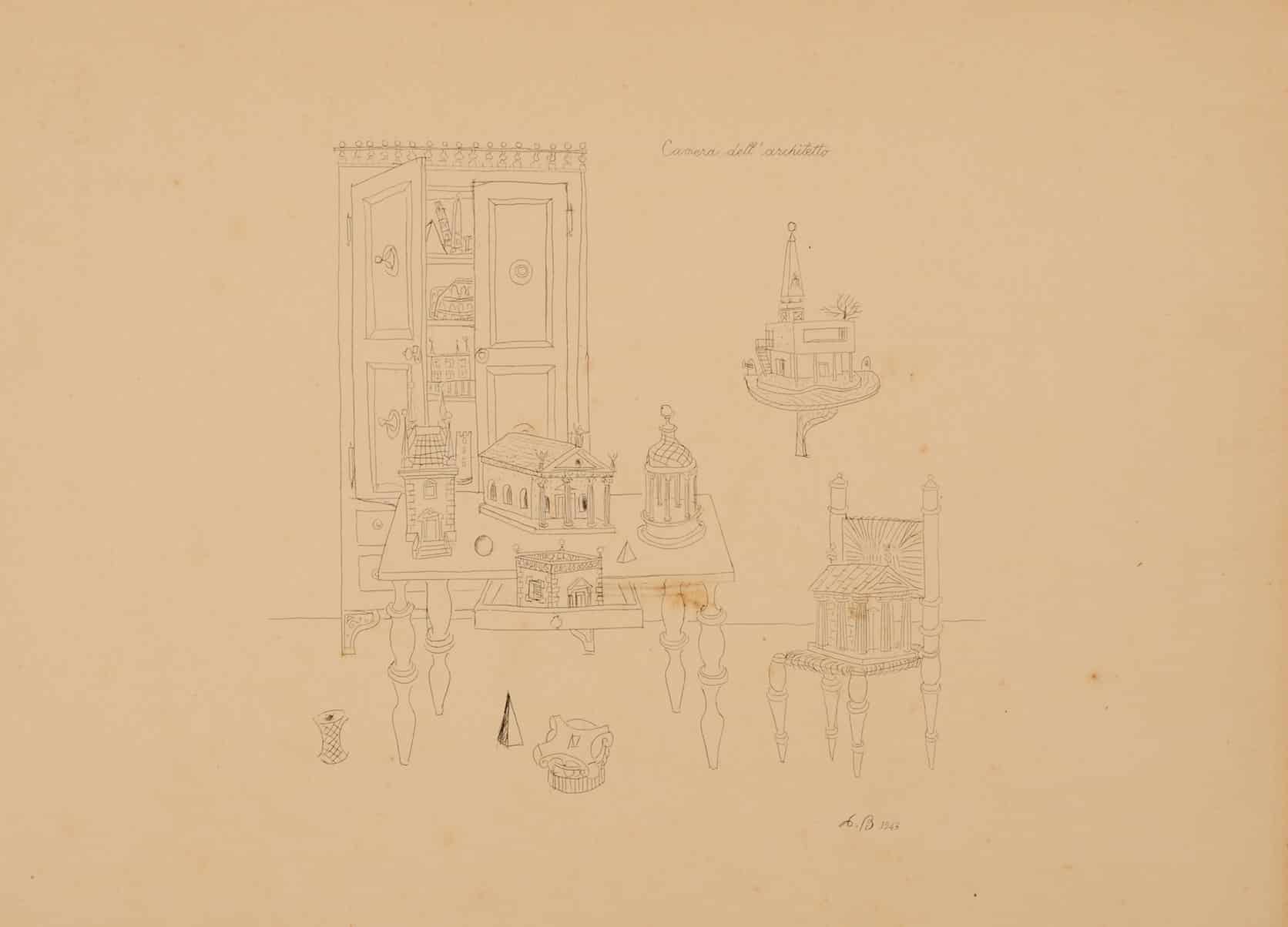

The author of the cartoon may well have broken a sweat if confronted with this sketch by Lina Bo Bardi from 1943, titledPhotographic camera dell'architetto (Architect's room). In the foreground a tabular array is happily burping fully formed buildings, clown-car-like, from its i –one! – drawer. The surface is already then crowded that several others have been forced to decamp onto a nearby chair or the floor to make room. In the background an ornate armoire has been left open up to reveal however more buildings haphazardly stacked inside. Or maybe its inhabitants opened the door themselves to go a look at the latest inflow: on the pinnacle shelf we can encounter what appears to be the Tower of Pisa peering round an obelisk in pursuit of a meliorate view. The design of the piece of furniture points towards a domestic interior – what I am naming equally a desk could just as easily exist a dressing table; the armoire a wardrobe. Indeed, the title does not requite away what the function of this room might be, simply that it is occupied past an architect. Nosotros don't know whether the cartoon was made before or later a bombing raid severely damaged Bo Bardi's Milanese studio in August that twelvemonth, merely it's not hard to imagine that the struggle to maintain a fledgling architectural do during the war years might have left the young architect with a hard-headed attitude towards her own workspace. Any room volition do, Bo Bardi seems to be proposing, and then long as yous have enough ideas to fill up it.

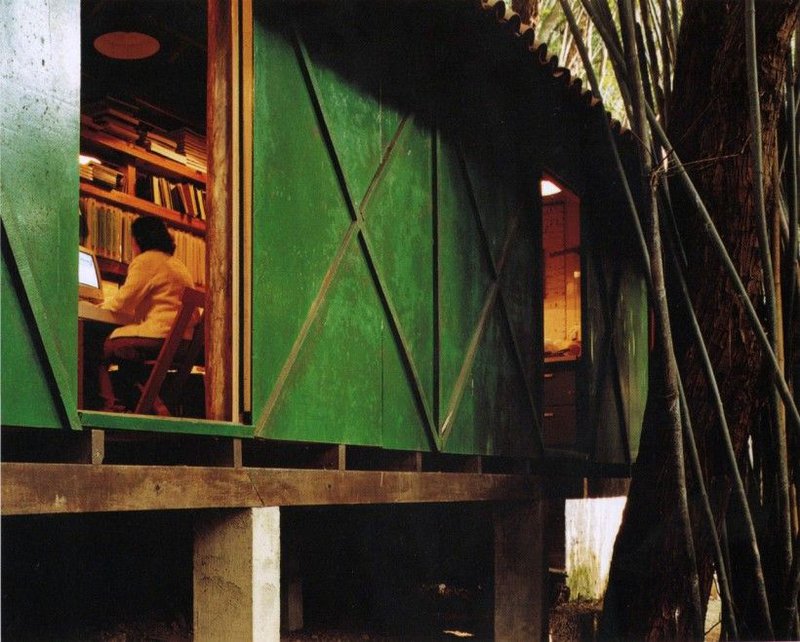

Virtually of the buildings depicted are drawn from classical architecture with i noticeable exception: a modernist villa that sits elevated on its ain individual isle abroad from the others. The upper branches of a tree are only visible behind the house – an early case of the 'perfect correspondence' between modern architecture and nature which came to ascertain Bo Bardi's architecture. Raised upwards above the others with an external staircase, narrow pilotis and a huge ribbon window, its design and setting are not unlike to the villa known as the Drinking glass House, which Lina went on to build on a hillside overlooking São Paulo 7 years later. There, a tree punched up through the center of the house and expanded to a dumbo rainforest that enveloped the property over the post-obit decades, today rendering information technology about invisible from the route. When Bo Bardi added a separate studio to the grounds in 1986, she chose sliding wooden panels over windows and then the sounds and smells of the surrounding copse could permeate the infinite.

'I ever stay half in the clouds, with only one foot in the city', wrote Calvino. What Lina's room and Italo'southward island accept in mutual is an agreement that where we happen to exist is not always where we actually are, though the atmospheric condition which keep us firmly grounded in one identify are very often the same ones that let us to drift off somewhere else. The absent-minded architect who occupies Bo Bardi's room is able to shuttle back and forth from Ancient Rome simply past opening a cupboard door, whilst the owner of the writing table tin can muffle within its orderly divisions a personal annal far more reliable than the dusty drawers of memory will allow. Calvino's desk, meanwhile, was positioned at the stop of the written report where the large picture window looking downwards onto the street gave way to a narrow horizontal discontinuity. When seated at his desk, the view through this pane would have been i of uninterrupted sky: the passing clouds could accept just as easily been hovering to a higher place thirteenth century Venice as twentieth century Paris. Which, of course, they were.

Notes

Further reading

Sara Ahmed, 'Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology', GLQ: A Periodical of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol 12, no 4 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), pp 543–74.

Lina Bo Bardi, 'Architecture and Nature: The House in the Landscape',Domus 191, November 1943.

Italo Calvino,Hermit in Paris (London: Penguin, 1994).

Esther da Costa Meyer, 'Subsequently the Alluvion',Harvard Blueprint Magazine sixteen, 2002.

Francine du Plessix Gray, 'Visiting Italo Calvino',The New York Times, June 21 1981.

Damien Pettigrew and William Weaver, 'Italo Calvino, The Art of Fiction No 130',TheParis Review 124, 1992.

Source: https://drawingmatter.org/surface-oriented/

0 Response to "Italo Calvino the Art of Fiction No 130 Pdf"

Post a Comment